This is the story of Ekaterina, or if you prefer, Catherine II, the greatest of Russia.

Catherine II of Russia, the great; one of the most interesting figures in the history of humanity. Catherine was a powerful, cultured, pragmatic and free woman. This is her story.

From Sofia to Ekaterina

On June 28, 1744, in the Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul, Sophia left behind her identity as a member of the German lower nobility to effect her conversion from the Lutheran faith to the Russian Orthodox Church. This conversion was one more of the obligations that she had to fulfill within the objective for which she was there, to marry the heir to the throne of the Russian Empire.

After the rite, Sophie Friederike Auguste von Anhalt-Zerbst was left in the past and a new story began as Ekaterina Alekseevna Romanova.

Elizabeth

Yelisaveta, or well, Elizabeth, daughter of the legendary Peter the Great, became tsarina after a coup d’état. Elizabeth was a great sovereign, overshadowed by being in the middle of two monumental figures, her father and her niece/daughter-in-law.

As was often the case in the monarchies of those times, the lack of children made Elizabeth’s position unstable, so she had her nephew Peter, the son of her beloved sister Anne, called to name him successor.

Pedro III

The tsarevich who hated his homeland

Peter, raised in the kingdom of Prussia within the German culture that he idolized, instead of the handsome and vigorous prince worthy grandson of Peter “The Great” that the tsarina expected, was a weak guy with childish behavior who detested Russian culture.

The crown prince was raised with the idea that his ancestral homeland was a barbaric, dark and backward land, the opposite of his beloved Germany, he was not interested in living in and ruling Russia.

The ideal profile

Elizabeth had to find a wife for her heir and the chosen one was Sophie, from a noble por family, just like the Romanovs liked her. Royal blood without enough power to cause problems.

Sophie and her mother arrived at the Golovin Palace in Moscow and met Elizabeth. The tsarina felt almost immediate rejection by her mother, but the sympathy between the tsarina and the young woman was immediate. Sophie, our future Ekaterina, understood the opportunity and put effort into preparing for her future role.

Russian by conviction

While Peter, her fiancé, detested everything that was Russian, Sophie had an immediate adaptation to the culture and customs of her adopted country. She put effort into learning the language, to the point that she became ill from spending the nights studying the Russian language while she wandered barefoot on the icy floors of the palace and unabashedly adopted Orthodox religiosity, gaining the favor of Tsarina Elizabeth.

In her own memoirs, Catherine wrote that she recognized that she was not the most beautiful woman but she had plenty of charisma.

The Lioness and the pathetic guy

On August 21, 1745, Catherine, aged 16, married Peter, aged 17, in the most luxurious party the Russian Empire had ever experienced. Ekaterina wore a spectacular silver brocade dress that is now on display in the Moscow Kremlin museum.

The wedding was worthy of a fairy tale but the wedding night would be pathetic. According to her own memories, Ekaterina displayed her charm in bed, but hours passed before Pedro burst in, totally drunk.

Pedro barely realized Ekaterina’s presence and what she was willing to do with the consummation of the marriage. Pedro was willing to deploy a huge army of Prussian tin soldiers.

For 8 years, the nights inside the Tsarevich’s and his wife’s room were filled with toy military maneuvers and lacking passion. Ekaterina was a lioness and Peter a trash.

Legitimacy

Peter had no interest in Catherine, his passion was Prussian military pomp and getting drunk with his entourage of German lackeys, a situation that put Tsarina Elizabeth very tense, desperate to secure the succession with an heir… well, let’s clarify, a heir to his taste, because 700 kilometers from Saint Petersburg, in a dungeon of the Shlisselburg fortress, there was already a legitimate heir: Ivan VI, grandnephew of Peter “The Great”, who for 400 days was, from his cradle , Tsar of All the Russias until Elizabeth, whose pride and desire for power could not tolerate the crown being in the possession of a nursing baby, organized a coup d’état.

Elizabeth was not a sadist and she could not order the death of a baby, although she took care of erasing anything that reminded him of the legitimate tsar and kept him imprisoned throughout her life.

This made Elizabeth obsessed with Ekaterina getting pregnant. She anticipated the rumors of Peter’s impotence and as an act of empathy with Ekaterina, the queen put in her path her first lover, Sergei Saltykov, a handsome boyar from a family loyal to the Romanovs since ancient times. It took 9 years for the marriage between Peter and Ekaterina to be consummated.

La sucesión

Fruit of an horrible marriage, Paul was born, who was just as unattractive and weak as Peter, confirming his paternity (a miracle that occurred) despite the fact that Ekaterina swore in her memoirs that he had the bearing and grace of Saltykov. The baby barely lasted in her mother’s arms: Tsarina Elizabeth took him away from her and kept her under her strict guardianship.

Elizabeth felt sympathy for Catherine, but in the end, the reason for her presence at court, to perpetuate the Romanov line, had been fulfilled, so the risk of being considered expendable was great.

The tsarina would no longer show the interest she had before and her pathetic husband had never cared, but he was also not going to resign himself to having all her work to leave her native culture, language and religion being thrown away, which is why, Ekaterina had to prevail.

Ivan VI y Pedro III

The death of Elizabeth

Isabel already had the heir, but it was not the end of her problems. The tsarina, who was already of a certain age and whose health was deteriorating due to her love of drink, tobacco and abundant meals, had the Russian Empire embarked on the Seven Years’ War, the first global conflict in history, engaging with the bellicose Prussia.

Elizabeth feared that her nephew, sickly in love with German culture and a professional hater of Russia, would throw away what his father, Peter “The Great,” had cost so much to build, which is why she intended for the crown to pass directly to her grandson Paul and Ekaterina, whose potential he recognized, was regent. At that moment, her advice stopped her. It wasn’t the right time.

In the end, Elizabeth I, Empress of All Russia, died on January 5, 1762 at the age of 52.

Peter III

Elizabeth had every reason to distrust Peter, who, supported by his unhealthy Germanophilia, the first thing he did after being proclaimed tsar was to stop the war with Prussia just when the Russian victory was imminent, with the imperial army at the gates of Berlin. also signing a peace that was not beneficial to Russia and returning to the Prussians all the territories conquered during the war, a maneuver so disconcerting that the Prussians themselves did not believe it.

Peter was willing to strip Russia of all its cultural identity and Germanize the country. He intended to replace the Orthodox Church with the Lutheran confession and forced the Orthodox clergy to shave their beards. In the present we see it as ridiculous but it was a colossal transgression of Orthodox traditions. Furthermore, Peter spoke only in German and detested the Russian language, of which he barely knew a few words and filled the court with Germans.

It was logical that in a matter of months, the bravest boyars, the Russian feudal nobility, would turn against him.

Pedro III y su tormentosa relación con el clero ortodoxo

Catherine’s path

Although the Russian nobility was very conflictive, a Russian cultural trait is respect for the legitimate figure of the ruler, which is why they began to prepare the way for Ekaterina, the tsarina consort, and no one else, to occupy the throne.

Ekaterina had taken a path opposite to that of Pedro. She was fascinated with Russian culture, customs and language and over the years of her marriage, she had built loyalties and a reputation at court.

She was a cultured woman who devoured knowledge by reading the classics and thinkers of her time, maintaining correspondence with people like Voltaire and Diderot, becoming related to an ideology that was gaining great strength, the Enlightenment.

The first lovers

This is where only the issue of Catherine and her lovers become important. This woman suffered a terrible marriage, but when choosing lovers she was very precise, since they were not only men who satisfied her intimately but also who contributed to her interests.

The first was the already mentioned Sergei Saltikov, the vigorous boyar. Later she gave her passion to the British diplomat Charles Hanbury Williams and when she was Tsarina, it was Stanislaus Poniatowski, a Polish nobleman who was one of her great supporters and who in exchange gave her the throne of Poland where she reigned as Stanislaus II. . Yes, Elena Poniatowska descends from that family, specifically from Andreas, Stanislaus’s brother.

Ekaterina would reward very well the men who satisfied her as a woman and who served her well as Tsarina.

The Orlovs

Her next lover was General Grigori Orlov, a member of one of the most prestigious military dynasties in Russia. Orlov and his four brothers, also soldiers, were highly respected in the military leadership and gained the loyalty of the armed forces for Ekaterina.

The Orlovs knew of the military discontent against Pedro after the bungle made with the peace with Prussia and the Germanization of the army and they orchestrated a coup. Pedro was doing his thing, getting drunk with his lover, Isabel Votontzova (yes, even he had a lover). Catherine knew all this thanks to the fact that one of her confidants was the same sister as her husband’s lover. Anyway, palace issues.

Potiomkin dando su espada a Catalina durante su discurso previo al golpe.

The hit

According to Catherine’s memoirs: Fyodor Orlov warned the Tsarina that Grigori was in command of a regiment ready to depose Peter and that it was time to carry out the coup. Catherine rejected a dress that was offered to her and opted to dress in the green jacket of the legendary Preobrazhensky Regiment, one of the two that made up the Imperial Guard, the most important elite unit of the Russian army. She knew that this symbol was the ideal counterweight against the attack on Russian symbols that Peter perpetrated.

Ekaterina, who at that point spoke Russian almost like a native and on the back of her horse before 12,000 soldiers gave a speech where she praised the homeland and Russian culture with which she made the regiment vibrate.

In this emotional moment, there was a small detail. Catalina’s sword did not have the grip strap, thus creating the possibility that it would fall in the middle of the speech, breaking all the emotion, but a young cavalry officer, noticing the detail, immediately gave her his. The officer’s name was Grigory Potemkin.

The queen appreciated the detail and Grigori Orlov, the lover jealous of the gallantry of another of lower rank and because his position as favorite was fundamental to his interests, was not amused, so during a game of billiards, he and His brothers beat Potemkin so brutally that they left him blind in one eye. Potemkin would be sent to the other end of the empire, where he built himself and gained great prestige and would return in time to be very important in this plot.

Peter’s “accident”

Peter did not take the overthrow of him badly. In reality, governing a nation that he hated did not seem interesting to him, much less spending energy defending his crown, which is why he only asked to be allowed to leave for his beloved Germany with his lover, his violin, his lapdog, and his servant and that he was supplied with Burgundy wine and fine tobacco.

Perhaps he was sincere but Catherine was not going to trust him, so she confined him in Ropsha’s palace. At that time there were two legitimate tsars of Russia imprisoned, Peter, and Ivan.

Three days later, her lover, General Grigori Orlov, wrote to Catherine to warn of the “unfortunate” death of her husband.

Orlov classified it as an accident although the forensic analysis, which already existed in 18th century Russia, ruled that Pedro’s body was beaten and showed signs of strangulation, although in the official document, the stated cause was… well, an attack of hemorrhoids.

Catherine’s responsibility

According to communist historians of the Soviet era, “poor little” Pedro was a helpless victim of the “merciless and depraved Tsarina”… but hey, this is the typical mental milkshake of communists, capable of exalting and victimizing, by ideology, a filth like Peter and a current of modern historians also emerges who have wanted to absolve Ekaterina of the act.

It may be that the Orlov brothers, exasperated by Pedro’s striking petulance and stupidity, beat him up and went too far… but it is not unreasonable that they did it by executing an order from Catherine, because in the end, if she let Peter go, it was a matter of time before he would be co-opted by the Prussians to overthrow Ekaterina and in the end have a tsar completely sympathetic to their cause and with the added bonus of being legitimate.

If Catherine had Peter murdered, it was largely to prevent him from attacking her. Anyway, let’s not forget that this is how the world worked in the 18th century and in general, prior to the second half of the 20th century.

Consolidation

Catherine, preventing popular discontent in the face of a possible regicide, since in the end, as we said, Russians tend to be very loyal to their autocrat and according to chronicles, the rumors were fueled at the same funeral of Peter, who had his neck suspiciously covered. with a scarf, creating the rumor that the strangulation marks were being hidden, visited the little tsar held captive by the late Tsarina Elizabeth and after verifying that he was a poor unhappy life who was living his twenty-fourth year of age, captive since he was a baby, he asked reinforce your security.

No one could know about Ivan but it was impossible, since at court, there was a faction against Ekaterina that rose up in a rebellion in favor of Tsar Ivan VI, imprisoned since he was a baby, organizing a raid with the soldiers of the fortress where he was held. to release it.

The rebellion was crushed by the Imperial Guard, aligned with Catherine, and Ivan ended up dead. There were no longer any living claimants to Ekaterina’s throne, as she had been crowned in Moscow’s Dormition Cathedral on July 9, 1762 with the name Ekaterina, well…. Catherine II, but her power was consolidated with the deaths of Peter and Ivan.

Ekaterina’s goal was to follow the path of Peter the Great and his mentor Elizabeth. Modernize and Westernize the mammoth and in many ways backward Russian Empire.

Empress of All Russia

Ekaterina was sincerely in love with Russian folklore and culture, but she also knew that it had to be stylized and modernized by opening up to the trends of the Western world. She ordered the creation of a pavilion at the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg, her residence, in which she stored works of art by Rubens, Rembrandt and Raphael and which today is one of the most important museums in the world, the Hermitage. She also organized gatherings where hierarchies were forgotten and various ideas were expressed and discussed.

The empress was fascinated with the ideas of the Enlightenment, which is why she was a great promoter of public education, literacy, and founded the first school for women. She reformed the legislative bodies, secularized property of the Orthodox Church but even so, she did not lose ecclesiastical support, she also modernized the administration and implemented the use of paper money.

Always aware of the scientific discoveries of the moment, she was the first to be vaccinated against smallpox in Russia, in order to demonstrate to the population that they had nothing to fear from vaccines.

Illustration with measure

Let’s not be confused either, Ekaterina was fascinated with the Enlightenment, but in the approach of having knowledge and reason as pillars of the development of her court and of generating cultured and prepared elites to whom she delegated.

She would never question the autocratic figure of the tsars and apparently, the Russian people were not or are very interested in that either. What was an eternal headache for the empress and a huge obstacle to her modernizing plans was servitude. The medieval feudal system that still prevailed in 18th century Russia where peasants were tied to the land.

Catherine could not, for now, abolish serfdom because that would have caused an unprecedented political revolt.

Changes of that magnitude in general should be as least abrupt as possible and in the end, it was her great-grandson, Alexander II, who, after the disaster that the defeat in the Crimean War represented for Russia, abolished serfdom. The Russian Empire, with poorly armed and precariously trained serfs on the front, succumbed catastrophically to the free, well-trained and armed with the most advanced citizens that made up the armies of France and the United Kingdom, but that will be the subject of other installments.

The fury of the Cossacks

Those who, understandably, were not willing to be patient were the Russian serfs, the bulk of the population.

The Cossacks, warriors originally from the Caucasus and the steppes of Central Asia, protected the borders of the Russian Empire in exchange for some privileges and autonomy. They endured very harsh levies with their men and boys being recruited and used as cannon fodder for the giant imperial war machine that urgently needed troops to sustain its military efforts.

The Cossacks, despite collaborating, felt enormous contempt for the Russian state. Cossack Yemelián Pugachiov, originally from the banks of the Don, tired of being seen as cannon fodder, started a revolt which he legitimized by posing as the late Peter III.

In those times, 95% of the Russian population did not know what a tsar looked like, other than in the effigies on the coins and they did not question that this rough warrior with rustic manners could not, in any way, be a Romanov.

Pugachev’s revolt

Pugachev gathered a horde of one hundred thousand furious and bloodthirsty Cossacks, who, unlike other angry crowds, were ferocious soldiers well trained for war.

The rebellious Cossacks marched on Moscow and Saint Petersburg, destroying everything in their path along the banks of the Volga, massacring and raping men, women and children without distinction, whether they were rich boyars or poor peasants.

This is what always happens with social outbreaks that degenerate into waves of chaos and the most miserable violence that have little to do with a heroic end. Therefore, we must understand these revolts as part of the context of past eras, but we must avoid romanticizing them. Pugachev was about to reach central Russia, eventually occupying the important city of Kazan.

Ekaterina initially underestimated the revolt but understood his mistake and rectified it in time. The tsarina entrusted the job of suppressing that rebellion to that officer who had charmed her with her kindness and who was already a prestigious general and governor of Ukraine: Grigori Potemkin.

Potemkin suppressed the rebellion and put such a price on Pugachev’s head that he was handed over by his men. Pugachev was transferred to Moscow where he was tried and executed. With this success, General Potemkin would be a pillar in Ekaterina’s government.

Ekaterina and Potemkin

Historians agree that Potemkin was from Catherine’s life.

“You (Potyomkin) are so handsome, so clever, so cheerful and so witty! When I’m with you I don’t give any importance to the world. I’ve never been so happy.”

One of the great gifts that General Potemkin gave to his beloved wife was to give her the Crimean peninsula in 1783, as a result of the First Russo-Turkish War.

With this conquest, the dream of Peter the Great was fulfilled, that of seeing Russia with access to the Black Sea and, therefore, to the Mediterranean, finally having a coastline with ports that remain active all year round, in one of the areas most strategic in the world and without suffering the odious winter freezing of the Baltic ports.

The triumphal entry of Ekaterina into Crimea together with her ally, Emperor Joseph II of Habsburg of what remained of the Holy Roman Empire, caused resentment in Istanbul and the Ottoman sultan, harangued by the British and French ambassadors, restarted hostilities, starting to the Second Russo-Turkish War, which culminated in a new Russian victory and with Ekaterina’s empire expanding further.

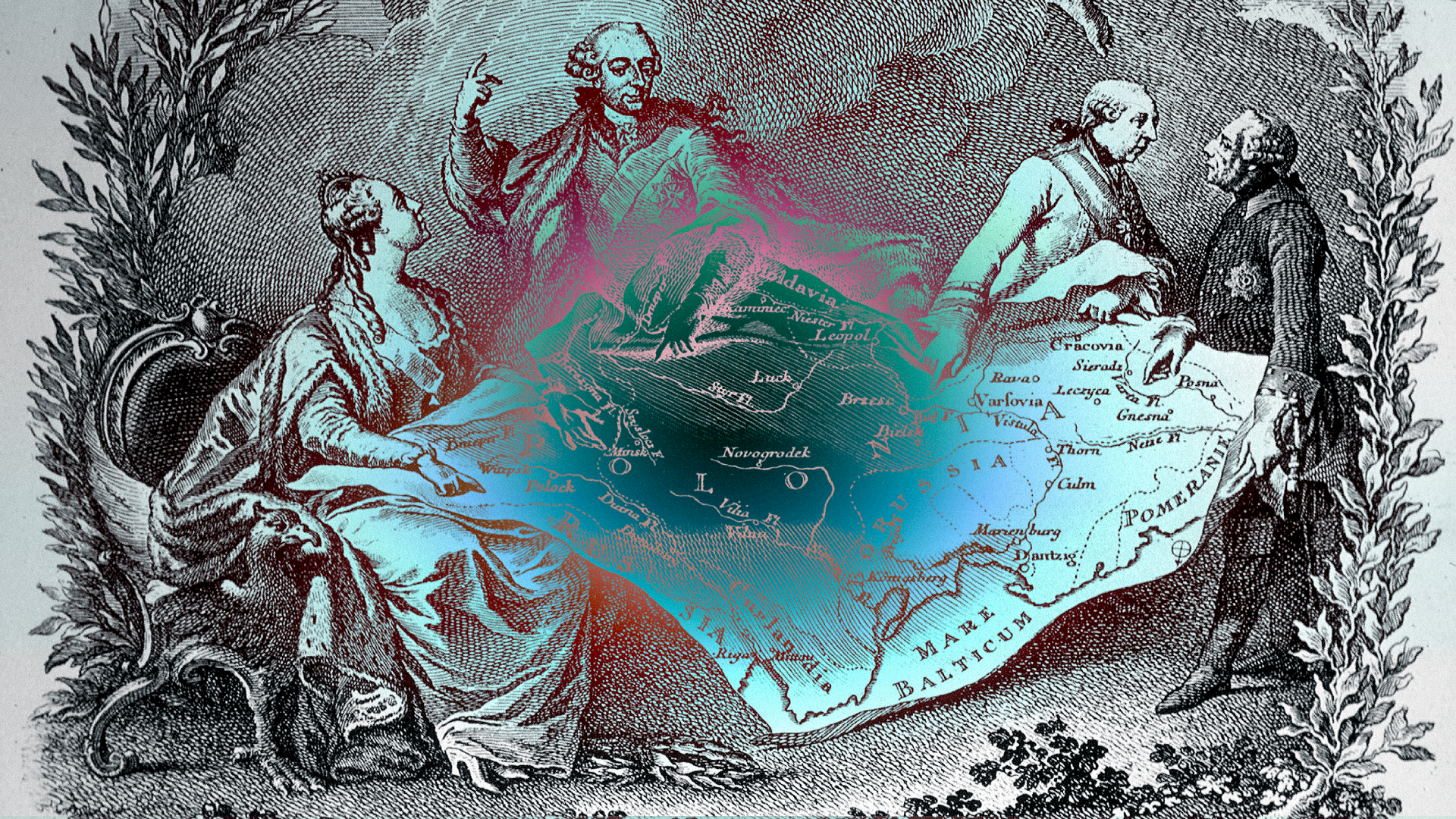

Russia controlled the northern coast of the Black Sea, and inevitably led it to subjugate Poland, a flat nation with irresistible fertile fields, as well as Lithuania, in the Baltic. Poland and Lithuania, with their unified crowns, made up at that time the largest nation in Europe. With this conquest, she increased the territory of the Russian empire until it became the largest of its time, although this would actually bring more problems than solutions.

Polish troubles

Poland functioned as a buffer state, a land barrier between Russia and the bellicose Central Powers, Prussia and Austria. By annexing the territory, she stood wall to wall with the aggressive neighbors.

To avoid tensions, Catherine, on behalf of Russia, in addition to the sovereigns of Prussia and Austria, de facto eliminated Polish sovereignty and divided its territory up to 3 times, with Stanislaus II Poniatowski, former lover of Ekaterina, being the last king of Poland. and obviously, without consulting the Poles. The areas of Poland and Lithuania that passed under Russian sovereignty include present-day Belarus and Livonia.

Poland was a headache for Russians, Prussians and Austrians alike. The Poles were a people heir to a military power, with their own language and culture and mostly Catholic. The Poles rebelled constantly well into the 19th century and almost into the 20th century, giving Ekaterina and her successors many problems.

Ashkenazi

By annexing Poland, another problem arose for the tsarina to solve, this time of a social nature. Poland was a state whose society was made up of many nationalities and it was already difficult to “Russify” the vast territory they had, with the greatest complexity being the issue of the enormous community of Polish Jews.

From the founding of the Kingdom of Poland in the 11th century and until the Polish-Lithuanian union that began in 1569, Poland, one of the historical bastions of Catholicism in Central Europe, was one of the most tolerant countries in Europe towards Judaism, becoming the home of one of the largest and most prosperous Jewish communities in the world, the Ashkenazi.

These Jewish communities were gradually losing tranquility and Polish tolerance was diminishing due to their geographical position, in the middle of the hottest area of conflicts generated by the Protestant Reformation and the Counter-Reformation launched by the Catholic Church after the Council of Trento in that disastrous 17th century deeply infected by religious conflicts. With the final annexation to the Russian Empire their rights were simply withdrawn.

Catherine, anti-Semitic?

Catherine suppressed the rights of Jews within the empire in 1742, becoming classified as a foreign population. On January 3, 1792, a decree was issued that forced Jews to live confined to the westernmost end of the empire, called the “settlement zone,” and they were prohibited from approaching the large urban centers of the Russian Empire such as Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Kazan, former Tsaritsyn, current Volgograd and Kiev. Something disastrous for a community of merchants and financiers.

Was Ekaterina anti-Semitic? It is likely that she did not have any special feelings for the Jews, adding that the Tsarina herself, so influenced by Enlightenment thought, did not live a devout religiosity, but as happened with the Catholic Monarchs in Spain, she faced to a context where the homogenization of societies in social, linguistic and religious matters was essential to become, according to the mentality of the time, a “civilized and governable” nation. Catherine, as with the issue of servitude, had to adapt and submit to the conventions of her time.

The problem is that although the Tsarina did not have any problem with the Jewish community, the rest of the nobility and the population did begin a stage of anti-Semitism, initiated by the State and which degenerated into discrimination and violence that reached its most critical point. already in the decline of the Empire, generating, once again, the repulsive pogroms.

Modernization

A pillar of Catherine’s government project was to encourage immigration to the less densely populated areas of the Empire. She was still German and she was clear that the Germanic states, Prussia and Austria, had a higher level of development and modernity than Russia. During the 1760s, Catherine’s government invited waves of German migrants to settle in the Volga area.

A century later, her grandson, Tsar Alexander I, would replicate the same action but in the Black Sea area, the new jewel of the Russian Empire.

José II, Archiduque de Austria y Sacro Emperador Romano, Catalina II, Zarina del Imperio Ruso y Federico II, Rey de Prusia

Prestige

In Europe, Ekaterina II Romanova, Empress of all the Russias, was a respected sovereign. Her neighbors, Austria and Prussia, avoided confrontation with the Tsarina who was a mediator in the War of the Bavarian Succession between both Germanic powers.

Catherine resisted the failed attempt by her cousin, King Gustav III of Sweden, to recover the Baltic territories. The Ottomans do not dare to confront Russian interests and in the West, France and the United Kingdom cautiously monitor the new power. In this context, the British deal with the revolt that made their thirteen North American colonies independent. In France, the outbreak of the revolution is imminent. Catalina remained neutral in both conflicts, taking care that the revolutionary fire did not spread to her domain.

At the Asian end of the empire, Catherine maintained neutrality with the Chinese Empire of the Qing dynasty. Hunter settlers from the Kamchatka Peninsula and the Kuiriles and Aleutian Islands sought to expand Russian influence. They tried unsuccessfully to initiate trade relations with the isolated Tokugawa shogunate of Japan. Relations between Russia and Japan would be strained and would culminate in war.

Catherine’s empire crossed the Bering Strait and established itself in American territory, taking sovereignty of Alaska. A century later, this territory was sold to the nation founded by emancipated British settlers, the United States of America.

Stormy bonds

Despite her achievements abroad, at home, things did not look easy for the Tsarina, especially with her family. While Europe admired and feared her, her son and heir, Paul, looked down on her. Paul accused her mother of taking her father away from her… .. yes, it is obvious that we all need our father, but, oh, Paul, if only you had known how he was yours!

Catherine, replicating the actions of her mentor, Tsarina Elizabeth, sought to bypass her legitimate heir in favor of her grandson Alexander.

Ekaterina was not a very dedicated mother and she had very little affinity with Paul, who apparently was similar to her father. He was religious to the point of prudishness, obsessed with military pomp, and sour-tempered. Paul posed a profound threat to the advances and glory achieved by Peter the Great, Elizabeth and Catherine.

On the other hand, the Tsarina saw in her grandson, Alexander, a figure with enough talent and grace to become Emperor.

Caricatura británica satirizando a Catalina II, José II de Austria y Federico II de Prusia

Potemkin villages

It is said that Catherine secretly married General Potemkin, although this is unlikely. The couple lost their sexual connection over time, but were very close until his death in 1791.

According to detractors, Potemkin went around the empire setting up a false portable village as a propaganda act about the objectives of repopulating the conquered territories. There is no data confirming this fact under Catherine’s reign.

Sovereign of her intimacy

The Tsarina enjoyed her sexuality to the end of the day, perhaps more than many modern women, but no different from her male counterparts. It must be emphasized that the legends about her sexuality are nothing more than fake news invented by her detractors.

Catherine’s memoirs

The most pleasant thing about the character of Ekaterina II is that this type of gossip and black legend did not cause her the slightest harm. In her memoirs, also written in English and French, we have a fabulous document that tells us about her experiences in her own handwriting.

The Tsarina herself tells us about her twenty-one lovers and in some cases, she does not omit spicy details. In her handwriting there are mentions of her relationship with Ivan Rimsky Korsakov, the composer’s grandfather, or Platon Zubov, her last lover. Plato was a handsome twenty-something whose vigor was enjoyed by the sixty-year-old sovereign.

Catherine was a woman and ruler of the 18th century who managed an exercise in transparency that is rarely seen, even in our times.

The greatest

On November 5, 1796, Ekaterina got up, as always, at six in the morning to start her work day. She prepared the coffee and while she was getting ready to take a bath and then start her workday, she suffered a stroke. The brilliant mind of the empress did not come to her senses and after 12 days of agony, she died on November 17, 1796. She was buried, with all her honors, in the cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul in Saint Petersburg.

Paul, her son, became tsar. Paul was obsessed with his poor father figure and was resentful of his lack of maternal affection. Despite Catalina’s denial, Paul was very similar to him. He dressed in a Prussian uniform, was a Germanophile to absurd levels, and signed a law that prevented women from accessing the Russian throne.

The indelible mark

Paul I’s reign lasted 5 years after he was assassinated by conspirators. The conspirators gave the crown to his son Alexander. All his laws were repealed.

Neither Paul, the communists or the Nazis who invented legends about sex with horses erased the trace of this sovereign.

Ekaterina Alekseyvena Romanova, the greatest Empress of All the Russias.

Trailer de Catherine the Great. Serie producida por HBO donde la actriz británica Helen Mirren interpreta a la zarina Catalina II.